Community Engagement:

Embeddedness within the Arts and Culture Sector

Douglas R. Clayton, Senior Vice President

Calida N. Jones, Vice President

The majority of arts and culture organizations in North America are categorized as nonprofit because their first objective is to provide public benefits to society, rather than solely produce financial results. However, many of these organizations are challenged by creating art or providing cultural experiences that are reflective of the broader community in which they operate. Arts and culture organizations have identified striking discrepancies between the demographics of their engaged patrons and the specific communities that they should serve to meet the public benefit nonprofit mandate. Studies have shown an over-representation of the white, older, educated, upper class patron within the arts and culture sector.[1]

To change this dynamic, many arts and culture organizations continue to expand or reframe their core missions of producing or presenting arts and cultural offerings by investing in community engagement staff, programs, and initiatives. This trend leads to questions that these organizations should address: Who are the people we exist to serve? What goals do we have for our work with those groups or individuals? How can this engagement be authentic and impactful? This issue of Arts Insights, the first in a two-part series, explores the importance of community engagement within the arts and culture sector and how the idea of embeddedness can transform arts and culture organizations by authentically integrating these efforts seamlessly into the organization using techniques that staff and boards often already know yet are challenged to implement.

What is Community Engagement?

Community engagement, in its most successful form, ensures that those most impacted by organizational activities have a say in the design and implementation of programs and projects. The health and vitality of an organization could be measured by how connected it is to its entire community. This is reflective of the economic concept of “embeddedness,” Karl Polanyi’s theory that “the economy is not autonomous, but is subordinated to politics, religion, and social relations.”[2] In other words, the economic success of organizations is dependent, first and foremost, on the relationships that exist with their customers (or the communities they serve). These relationships need to be prioritized ahead of the product itself in strategic planning, budgeting, and resource allocations while keeping in mind that for some constituents, core elements of the product may be essential to maintaining strong relationships.

In addition, making the investment in community engagement can expand an organization’s stability and economic strength, as well as grow the cultural vitality in the region. According to the Urban Institute’s Arts and Culture Indicators Project, the definition of cultural vitality recognizes that arts and culture are “resources that come out of communities rather than merely resources that are ‘brought to communities from the outside.’”[3]

The Evolution of Community Engagement

Most organizations within the arts and culture sector are still growing in their understanding of why community engagement is critical and who reaps the benefits of decisions made in all activity areas. Throughout time, community engagement efforts have evolved. Decades ago, arts and culture organizations did not use the term “community engagement,” but instead focused largely on marketing in a transactional sales dynamic, less obviously pursuing community connections through more targeted frameworks, such as resident artistic companies, collaborative projects, shared programming, or civic partnership building. As time went on, organizations more intentionally engaged their communities through expanded and rebranded marketing efforts, which led to community “outreach” programs. As the field has grown, the impact of outreach—with efforts done for a community rather than with a community—has had varying levels of effectiveness. It has often only realized short-term benefits or gains, most epitomized by sales or attendance spikes during overt outreach periods, such as during Black History Month, which do not translate to long-term connections to the organization or financial stability.[4] As the field continues to evolve, the term “outreach” has largely disappeared from much of the vocabulary in lieu of “engagement” with efforts aligned with and for historically marginalized communities—racially, socially, economically, and so on.

In recent years, the community engagement model has transformed. Funding structures and budgeting in this area have become multi-year, allowing organizations to deepen their efforts over time. While there are positive outcomes to this development, organizations must challenge themselves by committing to authentic and responsive dialogue with community members and leaders. This includes preparing for the moments when community members express disinterest in programmatic offerings and developing alternatives that serve the community’s needs even when those are not what were previously planned.

The Continuum of Community Engagement

The initial question every organization must ask is: Who are the people we exist to serve? Ideally, this question should be answered in the organization’s mission statement. It should also be the first consideration in terms of not only community engagement efforts but also all artistic or administrative planning decisions. Once a group or groups of people have been specifically identified as the organization’s core constituents, an exploration of the style of relationship can begin. The following frameworks apply in many situations, whether the “who” centers on communities united by geography (such as a neighborhood), demographics, personal life experience, current profession (such as artists), or established cultural interest (such as existing supporters of an artform).

According to the Urban Institute, to more fully understand the dynamics of community engagement efforts, artists, staff, and boards should consider with the following questions:

- Is engagement ongoing or episodic?

- Do people participate as individuals or as a group?

- Is participation formal or informal?

- Do motives for engagement change or evolve over time? [5]

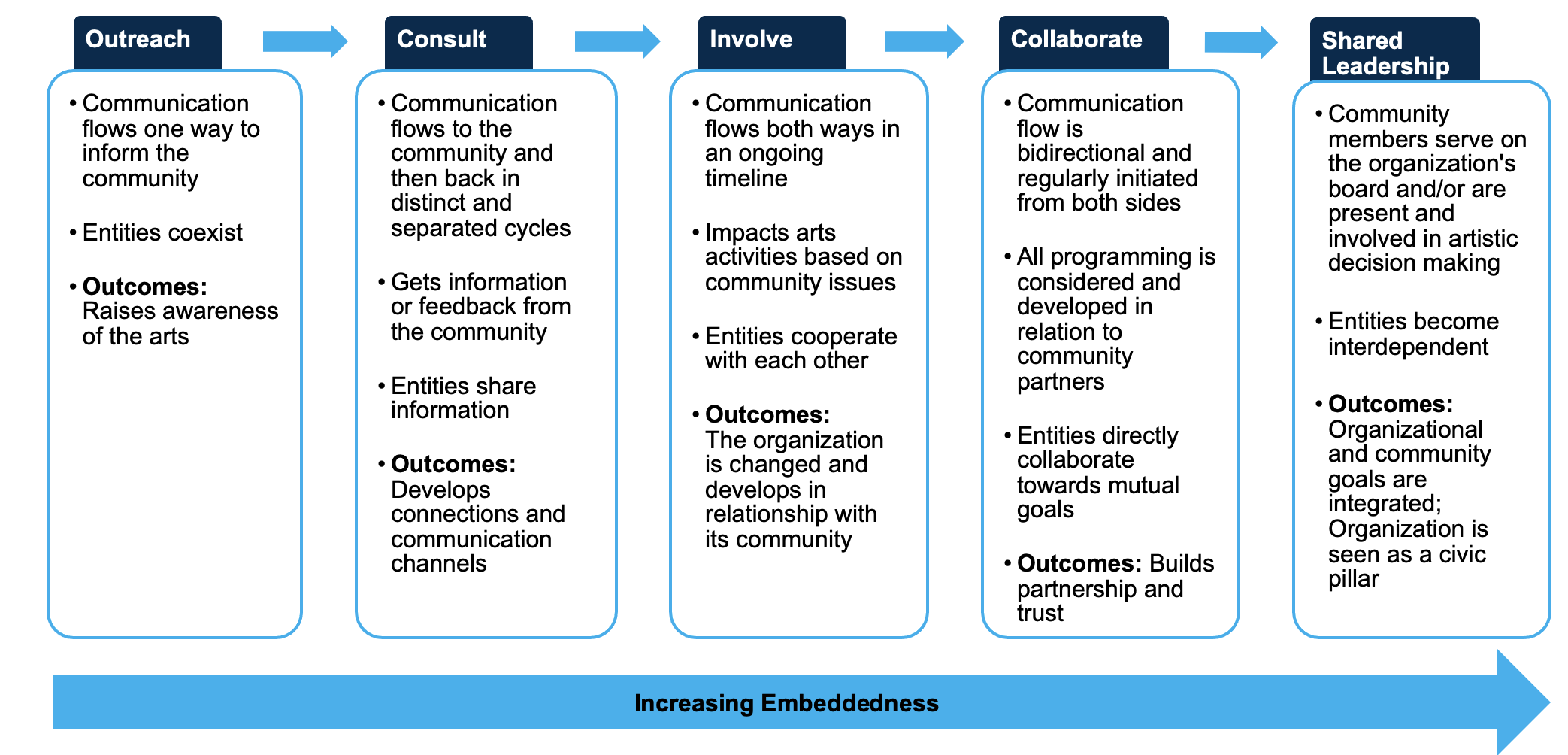

As the arts and culture sector has moved through transforming its community engagement practices, organizations can look to the Continuum of Public Participation model as defined by the International Association for Public Participation.[6] The following model has been adapted for arts and culture organizations:

To deepen embeddedness, arts and culture organizations can take the following steps:

- Consider whose voice is being heard. Diversity of thought needs to remain a constant goal especially when exploring community access points.

- Establish and communicate clear, transparent reasons for engaging the community. Take intentional steps to eliminate the possibility of performative behaviors.

- Determine goals and outcomes alongside community members. Often, arts and cultural organizations unintentionally override the community’s voice instead of amplifying those who are impacted the most.

- Choose an engagement strategy, provide clarity, and then follow through on those promises.

- Create opportunities for raising and discussing concerns. Regular, on-going interactions allow people to express concerns before problems become too big or get out of control.[7]

Conclusion

The first task for any organization pursuing community engagement is to identify who they serve and then where they currently exist on the Continuum of Public Participation. Today’s community engagement initiatives in the field largely function in the Consult and Involve phases. Arts and culture organizations often struggle moving forward through this paradigm—or even question why they should at all—given their current mission. As organizations face internal and external pressure to prioritize inclusion and relevance, they can clarify next steps by examining where they are on this continuum with their constituents. This process can highlight ways in which changes in communication, decision-making processes, and centering of authority are affecting the organization’s relationships and, by extension, its long-term embeddedness and organizational stability. To achieve true and authentic community engagement, organizations must meet regularly with the board, staff, artists, and stakeholders to discuss specifically how community engagement relates to their core missions and how artistic activities are perceived in the communities they serve.

The second part of this series will relate community engagement activities and framing to skills already present in most arts and culture organizations, as well as simple shifts of value and attitude that can make major changes in how embedded an organization is with its constituents.

[1] “A Decade of Arts Engagement: Findings from the Survey of Public Participation in the Arts, 2002–2012,” National Endowment for the Arts, https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/2012-sppa-jan2015-rev.pdf.

[2] Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time, (1944, Beacon Press).

[3] Maria Rosario Jackson, Florence Kabwasa-Green, Joaquín Herranz, “Cultural Vitality in Communities: Interpretation and Indicators,” The Urban Institute, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/50676/311392-Cultural-Vitality-in-Communities-Interpretation-and-Indicators.PDF.

[4] Doug Borwisk, “Outreach ≠ Community Engagement,” ArtsJournal, https://www.artsjournal.com/engage/2013/03/outreach-%E2%89%A0-community-engagement/.

[5] “Art and Culture in Communities: Unpacking Participation,” Urban Institute, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/59186/311006-Art-and-Culture-in-Communities-Unpacking-Participation.PDF.

[6] IAP2 Continuum of Public Participation, International Association for Public Participation, https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.iap2.org/resource/resmgr/pillars/Spectrum_8.5x11_Print.pdf.

[7] “Community Engagement for Collective Action: A handbook for Practitioners,” Invasive Animals CRC, Australia, 2007.

Editor’s Note: ACG thanks Kristian Roberts and Quodesia Johnson for their valued input on this article.

Douglas R. Clayton, Senior Vice President

Douglas R. Clayton, Senior Vice President

Mr. Clayton joined ACG in 2019, bringing more than 20 years of experience in the arts and culture industry, specifically within opera, theater, and arts service organizations. Passionate about innovative business models in the arts and culture sector, he leads ACG’s Planning & Capacity Building area, guiding strategic planning and community engagement, facilities and program planning, organizational benchmarking studies, board governance summits, team building retreats, and a variety of services that strengthen nonprofit organizations, universities, government agencies, and the communities they serve. Mr. Clayton has an extensive background in cross-sector collaboration in public-private partnerships and the dynamic relationships that exist in the creative industries. Prior to joining ACG, Mr. Clayton served in various roles at Chicago Opera Theater, ultimately becoming General Director. He has also served as Director of Programming and Operations for LA Stage Alliance, as Chair of the Host Committee for the record-breaking 2011 Theater Communications Group national conference, and as a member of the Directors Lab West’s steering committee. Mr. Clayton has worked artistically as a stage director, playwright, and performer and has hands-on experience as both an artist and producer with a range of theatrical unions in the United States, including the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society, Actors’ Equity Association, American Guild of Musical Artists, and United Scenic Artists. Mr. Clayton holds a bachelor of science from the University of Southern California and earned a master of business administration from the Anderson School of Management at the University of California, Los Angeles. In 2018 he was named to Crain’s Chicago Business 40 under 40 list as a leading innovator in the business of culture.

Calida N. Jones, Vice President

Ms. Jones brings more than 20 years of experience in planning, workshop and curriculum development, project management, and advancing equity, diversity, inclusion, and access initiatives. She has provided strategic guidance to organizations across the country, supporting and assisting arts in the creation of equity, diversity, inclusion, and access goals. Ms. Jones previously served as the Director of Engagement of The Hartt School at the University of Hartford, where she implemented a faculty development training program, collaborated with the University’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion office, and curated external community partnerships with local and national youth arts agencies. She also served as Program Director for Music Matters and Conductor of the Hartford All-City Youth Orchestra in conjunction with the Charter Oak Culture Center, Director of Development and Advocacy for the El Sistema-inspired program PROJECT MUSIC, and Artistic Director of the Waterbury Symphony Orchestra’s El Sistema-inspired program Bravo Waterbury!. Ms. Jones currently serves as the President of the Connecticut Arts Alliance and as Board Clerk for El Sistema USA, where she also chairs the Racial Diversity and Cultural Understanding Committee. A TEDx speaker in San Jose, Ms. Jones has had the privilege of speaking at prestigious institutions such as Yale School of Music, Duke University, The Connecticut State Capitol, and The Hartt School. She has received numerous honors during her career, including a scholar fellowship at the Aspen Ideas Festival, Elizabeth L. Mahaffey Fellowship, Grammy Music Educator Award nomination, 2018 Connecticut Arts Hero Award, and the Father Thomas H. Dwyer Humanitarian Award for her work in Waterbury, Connecticut. Ms. Jones holds a bachelor of fine arts degree in violin performance from Indiana University of Pennsylvania and a master of music degree in violin performance and Suzuki pedagogy from The Hartt School.

Contact ACG for more information on how we can partner with your team through organizational assessments, strategic planning, or leadership coaching to set new structures and relational values that will deepen community engagement for your organization.

(888) 234.4236

info@ArtsConsulting.com

ArtsConsulting.com

Click here for the downloadable PDF.