Shaping a Resilient Arts and Culture Business Model: Is It Possible in a “Post-Pandemic” Artificial Intelligence World?

Dr. Bruce D. Thibodeau, President

The creation and implementation of a resilient business model in the arts and culture sector has sparked discussions, articles, and, for board and staff leaders, many sleepless nights. The public, private, and nonprofit sectors all face the challenges of an ever-changing “post-pandemic” world where COVID-19 cases continue, and Artificial Intelligence (AI) becomes more prevalent. For independent nonprofit organizations, dialog regarding resilient business models may develop from their vision to maximize artistic and educational impact with the financial, technological, and human resources to broaden inclusion and engagement. That may sound simple enough, so why is shaping a resilient business model so elusive?

For many in the arts and culture sector, the words “strategies, business models, and operations” are not clearly defined. The external context in which nonprofit organizations operate is becoming more challenging and competitive, although there are opportunities as society and technology evolve. Socially conscious nonprofits are shifting away from decisions based solely on past experience, industry norms, and resource dependency. Instead, they are creating innovative business models and practices by embracing strategic partnerships and community responses that include a deeper understanding of the internal and external forces that impact their organizations.[1] This edition of Arts Insights clarifies the differences between strategy, tactics, and business models and highlights several properties of a resilient business model. The information provided is intended to be the start of an ongoing dialog about the challenges and opportunities ahead for the dynamic nonprofit arts and culture industry.

Defining Strategy, Tactics, and Business Model

Organizational strategy, business models, and tactics can mean different things to various stakeholders. At times, these words are used interchangeably, which can create confusion in broader discussions around strategy and sustainability. The Harvard Business Review (HBR) article “How to Design a Winning Business Model” sheds important light on using strategy as the primary building block of competitiveness, arguing that the quest for sustainable advantage likely begins with the right business model. Strategy is the plan to create a unique and valuable position involving a distinctive set of activities, while the business model consists of how an organization creates and captures value for stakeholders. Tactics, sometimes referred to as operations, are the residual choices open to a company by virtue of the business model that it employs. If the business model for a ground transportation option is a car, then strategy is designing and building the car and tactics are how and where you drive the car.[2]

The Five Elements of Strategy

The article “Are you sure you have a strategy?” tackles issues related to strategic fragmentation, catch-all phrases, and statements that companies use as strategies when really referring to tactics. It is perhaps impossible to isolate specific elements of a strategy without looking at their synergistic whole. These elements include:

- Arenas: Where will an organization be active? In the arts and culture sector, this can take many shapes and forms both inside and outside its facilities, in its social media and digital presence, and well beyond.

- Vehicles: How will an organization get into those arenas? This may include collaborations, new program development, and any number of paths to reach a broader audience.

- Differentiators: What is an organization’s value proposition and positive institutional impact that will capture participation and support for its programs and services?

- Staging: What will be the speed and sequence of the organization’s actions?

- Economic Logic: How will the organization obtain its financial, social, cultural, community, and other returns in its quest to achieve sustainability?[3]

Key stakeholders with for-profit business savvy may believe the strategy is to run nonprofits “more like a business” with a financial bottom line as the primary goal. Experienced nonprofit sector professionals understand that the larger mission and intended institutional impacts can be constrained by a lack of financial, technologic, and human resources, all of which influence the business model. The reality of daily decisions, communications (in person and virtual), and relationships — as well as social change, environmental challenges, and advancing AI — can complicate these activities, creating an illusion that addressing short-term or urgent needs will achieve both the strategy and underlying business model. Such fragmentation does not advance the concept of what is inherently long-term sustainability or resiliency. Integrating the five elements into a cohesive strategy will allow for risk reduction in shaping a business model that can be adaptable. It also positions an organization to flexibly respond to changing social, technological, economic, environmental, political, legal, and ethical (STEEPLE) trends.

Policy, Asset, and Governance: The Choices and Consequences

Organizations generally make choices in three key areas when crafting their business models — policy, asset, and governance.[4] These choices can have flexible or rigid consequences. For example, discounted ticket pricing is flexible and could yield a short-term increase in attendance from a broader base, whereas operating in resource scarcity mode (i.e. under- or overworking staff) for extended periods of time can create a rigid and embedded expense-focused organizational culture rather than the pursuit of a vision with a realistic abundance mentality.

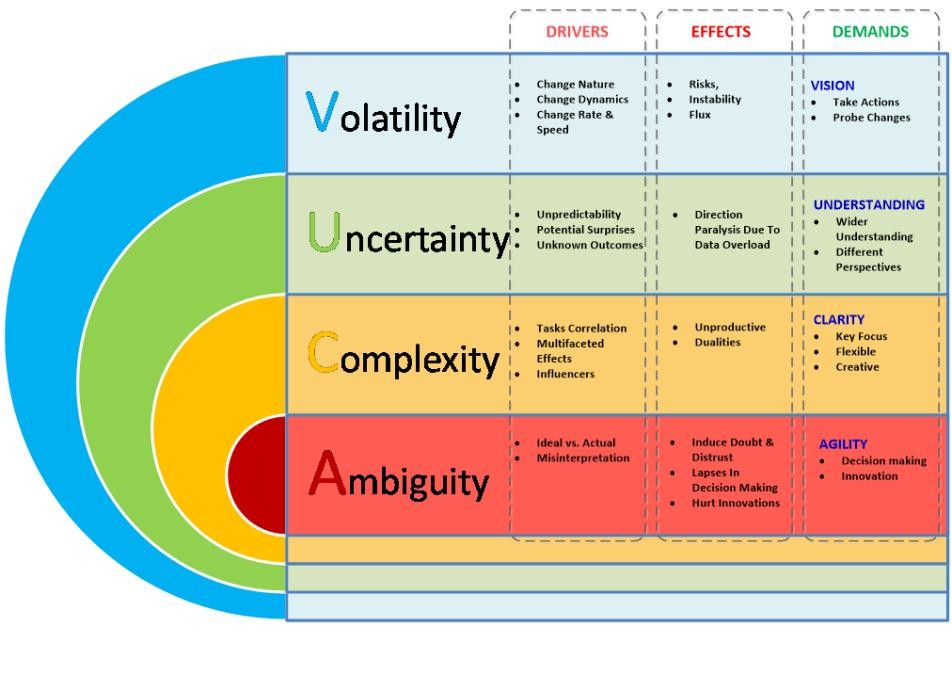

In another example, consequences can result from policies that seek to limit the use of unrestricted bequests into the permanently restricted endowment. But in volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA5) times, the policy can create a lean but inefficient business model that lacks the financial resources it needs to operate, achieve its strategic initiatives, and create long-term resiliency.

These endowment funds are typically held in trust to protect long-term legacy, but if an organization can’t sustain during VUCA times, policies may need to be reconsidered on how they are structured. Policy restrictions (choice) can become an impediment that creates unintentional negative results (consequences).

Choices and consequences in the nonprofit sector are perhaps even more pronounced and complex than in for-profits. Individuals in governance and policy roles can also provide or connect an organization with important financial, human, technological, or other material or intangible assets. Additionally, many of these key individuals are also consumers of the product or service offered by the organization for which they are setting policy and providing governance. While board members of international pharmaceutical companies may never use the drugs developed for patients, cultural institution trustees will immediately see the consequences of their choices. Running an arts and culture organization like a business takes on an entirely new meaning and creates far more intricate challenges for nonprofits in regard to strategy, tactics, and business model.

A Good Business Model: Are We There Yet?

Ultimately, the business model addresses who the customers are, what various stakeholders value, and how the organization delivers value to them.[6] If strategy is about designing and building cultural institutions and tactics relate to how they operate, perhaps the institution as “the car” is the most elusive analogy of the three to solidify. The following three questions can help determine the characteristics of a good business model.[7] Is the business model:

- Aligned with the organization’s mission and goals? Ultimately, does the business model enable building momentum towards the financial, cultural, community, social, or educational goals established as part of the strategy?

- Self-reinforcing? As an example, if a theater company believes its purpose is to provide low-cost access to its programs for those in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities but a majority of its seats are tailored to those with the means to pay, is the business model structured correctly?

- Robust? Can an organization capitalize on its strengths and opportunities while minimizing its weaknesses and threats (SWOT)? To achieve this, it is necessary to examine if the business model can fend off four key challenges: imitation (direct/indirect competitors), holdup (customers/suppliers bargaining), slack (organizational complacency), and substitution (new products/services).[8]

Organizations must consistently review various internal and external forces, their SWOT, available resources, industry changes, and the STEEPLE framework all while considering the quality and quantity of its programs and services. Focus should be directed at how effectively and consistently the cultural institution is delivering on its promises to the community and stakeholders that it serves and intends to serve.

Strategic Planning and Implementation Challenges

Members of the Academy of Management’s Strategizing Activities and Practice (SAP) have stated that strategy is not something that firms have but rather something that people in an organization do. Perhaps this is a further testament to the complexities of strategy, business models, and tactics that constantly require careful quantitative and qualitative research with different ways of thinking, learning, and doing business. Creating a meaningful strategy that has an innovative business model and effective tactical operations is not easy in the arts and culture sector. Private, public, and nonprofit practitioners struggle to comprehend the depth and breadth of complex issues that any business faces. All organizations hope to achieve sustainability and ensure resiliency by having an appropriate strategy, effective tactics, and the right business model. Through research, trial and error, and passion for their respective missions, arts and culture organizations can learn a tremendous amount about strategic frameworks, analytical tools, and organizational efficiencies. While challenging, the work must continue if these community pillars hope to thrive in a VUCA world.

Speaking of VUCA, Stanford Social Innovation Review published an article on how nonprofits are utilizing AI and its responsible adoption. Grant proposals, donor acknowledgements, newsletters, and press releases are among the areas where AI is being implemented. With this adoption, however, comes “reputational risks, especially if people don’t carefully review the text it generates before sharing it: results can be insensitive and offensive.” The article suggests several considerations before fully embracing AI, which include being thoughtful and well informed; tackling fears and anxieties; remaining human-focused; utilizing data safely; minimizing biases and risks; determining appropriate use; testing before full implementation; and redesigning jobs and associated learning in the workplace. As the article emphasizes, “a healthy workplace requires human connection, so professional skills development must include exercising emotional intelligence, empathy, problem formation, and creativity,”[9] all of which are hallmarks of the arts and culture sector.

Conclusion

A solid understanding of the dynamics within, across, and surrounding the nonprofit arts and culture sector will be one of the keys to its future success. The industry, institutions, and communities in which they operate have ever-changing demographics and socioeconomics that require careful consideration. As resources shift, local audience options expand, and live and virtual competition rise in the arts and culture sector, the factors that influence organizational resiliency are even more challenging. Focused strategies, efficient tactics, and well-defined business models must evolve—simultaneously learning from past experiences, living in an uncertain present, and looking to future opportunities. Extremely committed and socially active stakeholders continue to leave a tremendous legacy for the advancement of arts and culture as a cornerstone of resilient, diverse, and inclusive communities. Fortunately, their connection, capacity, and commitment bodes well for organizations that seek to realize impactful strategies and resilient business models into the future.

- Robert E. McDonald, Gillian Sullivan Mort, Jay Weerawardena, “Sustainability of nonprofit organizations: An empirical investigation,” Journal of World Business, 2010, 346-356.

- Ramon Casadesus-Masanell and Joan E. Ricart, “How to Design a Winning Business Model,” Harvard Business Review, January-February 2011.

- James W. Fredrickson and Donald C. Hambrick, “Are you sure you have a strategy?” The Academy of Management Executive, November 2005, 51-62.

- McDonald, Sullivan Mort, Weerawardena, supra.

- Warren G. Bennis, Bert Nanus, Leaders: Strategies for Taking Charge, Collins Business Essentials, 2007.

- Peter Drucker, “The Theory of the Business,” Harvard Business Rreview, September-October 1994, 95-104.

- McDonald, Sullivan Mort, Weerawardena, supra.

- Pankaj Shemawat, Commitment: The Dynamic of Strategy, New York: Free Press, 1991.

- Beth Kanter, Allison Fine & Philip Deng, “8 Steps Nonprofits Can Take to Adopt AI Responsibly,” Stanford Social Innovation Review, September 7, 2023.

Bruce D. Thibodeau, President

Founding ACG in 1997, Dr. Bruce D. Thibodeau (he/him/his or she/her/hers) provides strategic oversight of the firm’s Leadership Transitions, Revenue Enhancement, and Planning & Capacity Building areas. As President, he has guided hundreds of nonprofits, university, and government clients in effective executive searches, cultural facilities planning, fundraising and marketing assessments, strategic planning and business assessments, and board governance. Dr. Thibodeau is committed to a more inclusive, diverse, equitable, and accessible arts and culture sector and to the vibrancy of the communities served by these organizations. Dr. Thibodeau has also conducted extensive research in exploration of stakeholders, nonprofit arts management, and cultural facility project management to highlight how stakeholders influence and are influenced by nonprofit arts and culture organizations. His research and client work focus on how public and private dialogues between internal and external stakeholders prompt their iterative learning, deeper social and emotional bonds, and a sense of community built around shared project goals and mutually beneficial outcomes. Dr. Thibodeau has facilitated numerous community engagement processes that have increased the public dialogue and stakeholder awareness of the arts and culture sector’s value and its impact on communities. His expertise highlights the important roles of project champions and followers as they overcome inertia and gain momentum derived from their social connections, personal commitments, and financial capacities to support the sector. management roles at Boston Symphony Orchestra, Hartford Symphony Orchestra, Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra, Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, and Santa Fe Chamber Music Festival. A regular guest speaker at national and international arts, culture, and academic conferences, Dr. Thibodeau’s academic presentations include the Academy of Management and Social Theory, Politics, and the Arts, and publications include International Journal of Arts Management, and The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society. Dr. Thibodeau holds a doctorate of business administration from the Grenoble Ecole de Management (France), a master of business administration from the F.W. Olin Graduate School of Business at Babson College, and a bachelor of music from The Hartt School at the University of Hartford. He also has multiple certifications in competencies, communications, and motivations analysis from Target Training International. Dr. Thibodeau speaks conversational French, as well as basic Spanish and Portuguese.

Contact ACG for more information on how we can help your organization achieve its

strategic planning and community engagement goals through competitive market analysis.

(888) 234.4236

info@ArtsConsulting.com

ArtsConsulting.com

Click here for the downloadable PDF.